By Caitlyn Kirby

The US National Library of Medicine reports that 100 million scars are acquired by people every year. Yet each one of them has a different story behind it. Each one has a different shape. Each one brings a unique feature to its possessor.

Delta High School holds numerous people with scars. Some of these scars hold a sentimental value to students whether it is because of experiences the scar made them miss out on or just a funny story on which to reminisce.

“I see the body as a canvas,” junior Eleni Bow says. “I think scars, birthmarks, moles, things like that show who you are and what you do.”

Bow has hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (HEDS). This is a collagen deficiency that affects mainly skin, ligaments and joints. Because of this condition, her skin takes longer than usual to heal.

“I got this papercut about a month ago and it still is yet to completely heal. Even though it is healing it still has a scar,” Bow says.

Joint immobility is also a big factor with HEDS, and because of it her knee could dislocate anywhere and any time and there is nothing to stop it. When Bow was 9, she had a surgery that left vertical scars on both knees. The surgery was supposed to stop her knees from dislocating randomly, but unfortunately it did not work.

She says that explaining the visible scars and spots to people is the hardest part for her. People are so quick to come up with false assumptions.

“People will look at my legs and think a lot of different things like abuse, chicken pox, or poor hygiene when none of those things are true,” Bow says.

Despite all of the hardships that this syndrome has caused her both physically and mentally, she chooses to view her scars in a positive and profound way.

“When I look at the spots on my legs and I think, ‘These are disgusting,’ I’m almost like, ‘You know you could make constellations out of that and I think that’s really beautiful,’” she says.

Just as Bow thinks of her scars as beautiful, sophomore Grace Flowers does as well.

“It used to bother me and now I think it’s kind of cool. It’s part of what makes me me,” Flowers says.

She found a brown spot on her neck when she was in kindergarten. She later found out that it was a cyst on her thyroid duct. After having two unsuccessful surgeries at IU Health Ball Memorial Hospital, she went for her final surgery at Riley Hospital for Children. Finally, this surgery worked to remove the cyst, leaving two scars on her neck.

“If I didn’t get it removed it would have caused problems with my drainage/throat system,” Flowers says.

She says that since she was so young, she doesn’t remember much of her reaction, but her parents were shocked since it wasn’t common and they did not expect it.

Andrew Hewitt, a junior, was in sixth grade at a farm planting pumpkins for Halloween when he got some free time. The boys decided to split into two teams and play tag with sticks. If you got hit with a stick, you lost.

“We were throwing them really hard, like as hard as we could,” he says.

His brother cornered him, and as Andrew was trying to get away, he went past a roll of barbed wire. Andrew says he saw the barbed wire but thought he was far enough away from it. The barb left a big gash.

After he noticed how big the wound was he put a leaf over it to act as a bandage.

“We (him and his partner) sat behind bushes so they couldn’t find us and throw sticks at us while I was bleeding,’ Andrew says. ‘I put a leaf on it and we ate cucumbers from the garden nearby.”

When asked what he learned from the experience, all he says is “don’t run past barbed wire.”

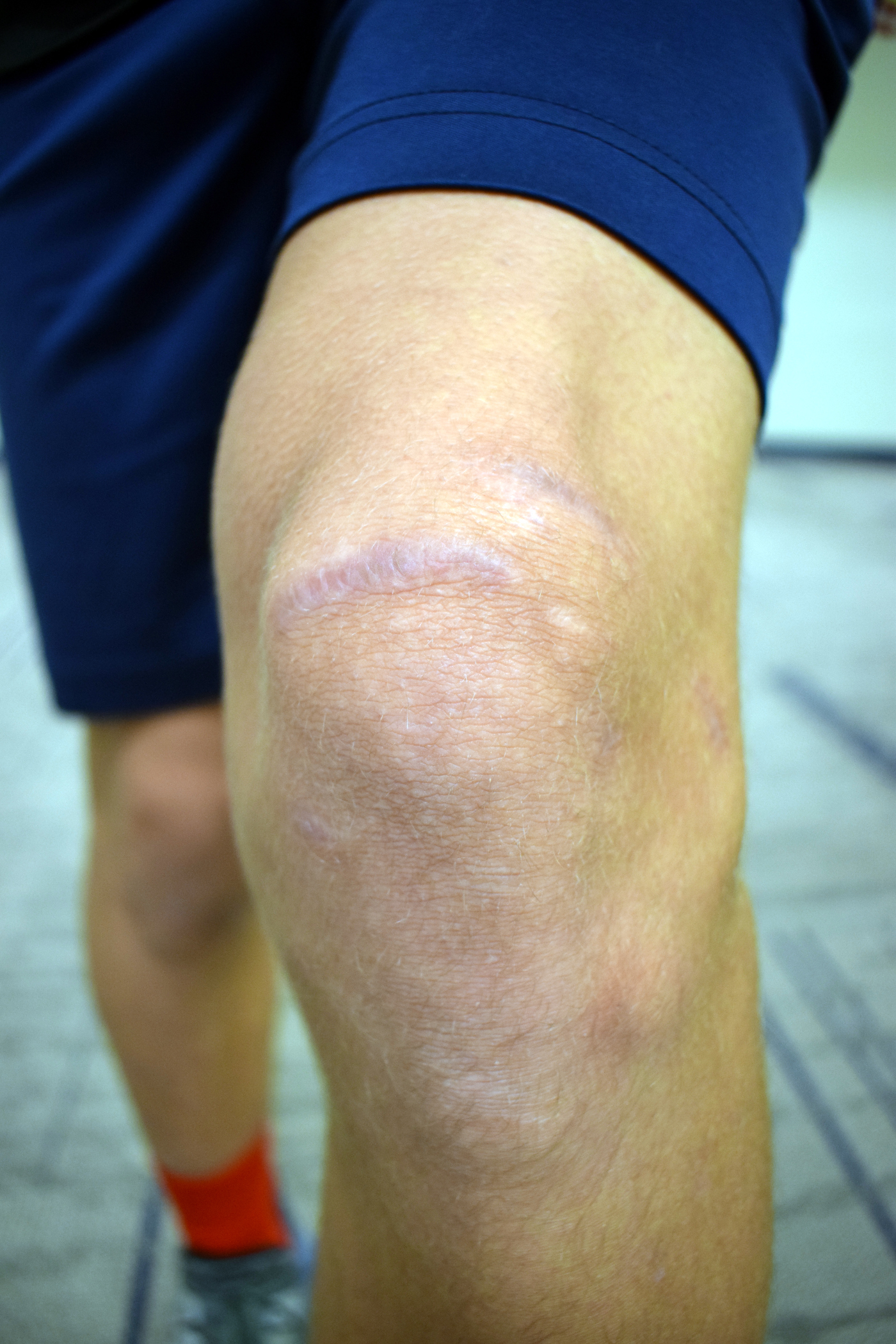

Parker Harris, another sophomore, hurt his knee in the middle of a baseball game in Columbus, Ind. He was in right field when the opposing team hit a pop fly. He went to slide in for the ball but the second baseman didn’t see him and stepped on his knee with his sharp cleats.

At first, Harris thought that he and the second baseman had just collided knees, but when the umpire came to ask him if he was okay, it turned out to be much worse than he had thought.

“I lifted up my pant leg and then you could just see white flesh,” Harris says.

He says that his teammates thought he was just being dramatic but once they saw his leg cut open with flesh showing, they were surprised to see he wasn’t just flipping out for no reason.

Because of his injury, Harris couldn’t play baseball for seven weeks and missed two tournaments.

“When I got back I couldn’t run as fast as I could or move as quickly because I didn’t really move when I was out,” Harris says.

Caleb Hewitt, a sophomore, was in fifth grade when he went mountain biking for the first time in the western hills of Michigan. When a group of more experienced bikers came up behind him, he moved over to the side to let them pass. However, he got too far over and fell.

When he got up he realized that the chain guard was broken and the chain of his bike had cut him and left a huge gash in his leg.

The scar doesn’t look that bad now, but when it first happened it was so deep the bone was visible, Caleb says.

Almost immediately after he saw the gash he fainted. One of the people he was with was a physical therapist so he quickly took action. He wrapped his sock around the wound and carried him over his shoulder all the way back.

“I’m fine with other people’s blood, but I guess not my own,” Caleb says.

Because of the stitches, Caleb had to miss out on some fun memories with his family. When they went to North Carolina a couple weeks later, he had to sit and watch everyone have fun swimming in the lakes and hiking in the mountains.

Through this experience, Caleb learned that in life you have to adapt to the things that happen to you, even if they are inconvenient or unwanted.

“When I look at the scar I think of life’s unexpected occurrences that you may have to adjust for,” Caleb says.